Mythology is the body of myths that have played a fundamental role in the development of society, culture, and civilizations. Myths have acted as foundational stories and to help explain the world in the absence of modern knowledge.

Myths started as traditional tales invented to explain specific beliefs, historical events, or facts of nature. Myths are as old as humanity, and historically they were endorsed by rulers and priests who linked them to religion or spirituality or the ruler’s authority for status.

Mythology in Art started in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt and was established as a popular art form by the Greeks in their sculptures.

Mythological Paintings emerged in popularity during the Renaissance when the great Renaissance masters added the humanist dimension to Greek and Roman mythology.

The development of mythological painting extended into the 19th century Romanticism, as well as the aesthetics of academic Art as championed by the significant European academies of fine Art well into modern times.

A Virtual Tour of Mythological Paintings

- “The Birth of Venus” by Sandro Botticelli

- “Venus at her Mirror” by Diego Velázquez

- “Diana and Actaeon” by Titian

- “Aurora abducting Cephalus” by Peter Paul Rubens

- Landscape with the Fall of Icarus – Pieter Bruegel

- The Triumph of Bacchus

- “Dido Building Carthage” by J. M. W. Turner

- “Venus and Mars” by Sandro Botticelli

- “Primavera” by Sandro Botticelli

- “Bacchus and Ariadne” by Titian

- “The Rape of Europa” by Titian

- “Perseus and Andromeda” by Titian

- “Perseus and Andromeda” by Joachim Wtewael

- “Perseus and Andromeda” by Giuseppe Cesari

- “Perseus and Andromeda” by Frederic Leighton

- “Perseus with the Head of Medusa” by Antonio Canova

- Cymon and Iphigenia by Frederic Leighton

- “Aurora and Cephalus” by François Boucher

- The Lady of Shalott by John William Waterhouse

- “Lady Lilith” by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

- Circe Invidiosa by John William Waterhouse

- “Hylas and the Nymphs” by John William Waterhouse

- “Pygmalion and Galatea” by Jean-Léon Gérôme

- The Judgment of Paris (Prado Museum)

- The Judgement of Paris (The National Gallery, London)

- “Battle of the Amazons” by Peter Paul Rubens

- “Leda and the Swan” by Paul Cézanne

- “Leda and the Swan” by Jerzy Hulewicz

- “Leda and the Swan” after Michelangelo

- “Leda and the Swan” by Cesare da Sesto, after Leonardo da Vinci

- “Leda and the Swan” After Leonardo da Vinci, Attributed to Il Sodoma

- “Leda and the Swan” by Francesco Melzi, after Leonardo da Vinci

- “Jupiter and Callisto” Attributed to Karel Philips Spierincks

- “Jupiter in the Guise of Diana, and the Nymph Callisto” by François Boucher

- “Diana and Callisto” by Titian

- “Diana and Callisto” by Peter Paul Rubens

- “Diana and Callisto” by Sebastiano Ricci

- “Diana and Callisto” by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo

- “Landscape with Diana and Callisto” by Cornelis van Pulenburg

- “Diana Discovering the Pregnancy of Callisto” Attributed to Paul Brill

- “Achilles on Skyros” by Nicolas Poussin

- “The Discovery of Achilles among the Daughters of Lycomedes” by Jan de Bray

- “Discovery of Achilles on Skyros” by Nicolas Poussin

- “Odysseus recognizes Achilles amongst the daughters of Lycomedes” by Louis Gauffier

- “Pallas and the Centaur” by Sandro Botticelli

- “Helen of Troy” by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

- “Medea” by Frederick Sandys

- “Tristan and Isolde” by John Duncan

Highlights Tour of Mythological Painting

“The Birth of Venus” by Sandro Botticelli

“The Birth of Venus” by Sandro Botticelli depicts the goddess Venus emerging from the sea after her birth fully grown. Venus is the Roman goddess of love, beauty, desire, fertility, prosperity, and victory.

In mythology, she was the mother of the Roman people through her son, Aeneas, who survived the fall of Troy and fled to Italy. Venus was central to many religious festivals and revered in the Roman religion.

The Romans adopted Venus from the myths of her Greek counterpart Aphrodite for their Art and literature.

In the later classical tradition of the West, Venus becomes one of the most famous figures of Greco-Roman mythology as the embodiment of love and sexuality.

“Venus at her Mirror” by Diego Velázquez

“Venus at her Mirror” by Diego Velazquez depicts the goddess Venus in a sensual pose, lying on a bed and looking into a mirror held by Cupid.

Painted by Diego Velázquez, the leading artist of the Spanish Golden Age, between 1647 and 1651, it is the only surviving female nude by Velázquez.

Nudes were extremely rare by seventeenth-century Spanish artists, who were policed by members of the Spanish Inquisition.

Despite the Spanish Catholic church’s restrictions, nudes by foreign artists were keenly collected by the Spanish court nobles.

This painting is also known by the titles of “The Rokeby Venus” and “The Toilet of Venus.” It was inspired by famous Italian works of the nude Venuses, which were the precedents for this work, which was painted during Velázquez’s visit to Italy.

Velázquez combined two traditional compositions of Venus in this painting, the recumbent Venus and the Venus looking at herself in the mirror.

“Diana and Actaeon” by Titian

“Diana and Actaeon” by Titian depicts the moment of surprise when the young hunter named Actaeon unwittingly stumbles on the naked goddess Diana who is enjoying a bath in spring with help from her escort of nymphs.

The nymphs scream in surprise and attempt to cover Diana, who, in a fit of fury, splashes water upon Actaeon.

As a mortal man, he is transformed into a deer with antlers and promptly flees in fear.

The myth of Diana and Actaeon can be found within Ovid’s Metamorphoses, which recounts the unfortunate fate of Actaeon, who, after fleeing, transformed into a deer he is tracked down by his own hounds and killed because they failed to recognize their master.

The story became popular in the Renaissance and has been depicted by many artists.

“Aurora abducting Cephalus” by Peter Paul Rubens

“Aurora abducting Cephalus” by Peter Paul Rubens depicts Aurora, the goddess of dawn stepping off her chariot to embrace Cephalus, a huntsman whom she was trying to abduct.

The story of Aurora abducting Cephalus comes from Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses.’ This painting is an oil sketch for one of a series of paintings commissioned by Philip IV of Spain to decorate his hunting lodge, just outside Madrid.

Rubens made extensive used oil sketches to explore and create design and composition concepts, and also as templates for the final full-scale canvases.

Peter Paul Rubens was a Flemish artist who is considered the most influential artist of the Flemish Baroque tradition. Rubens specialized in making altarpieces, portraits, landscapes, and history paintings of mythological and allegorical subjects.

His compositions referenced classical and Christian history and emphasized movement, color, and sensuality.

“Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” by Pieter Bruegel

“Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” by Pieter Brueghel, the Elder was long thought to be painted by Pieter Bruegel, the Elder.

However, following recent technical examinations, it is now regarded as an excellent early copy by an unknown artist of Bruegel’s lost original.

In Greek mythology, Icarus who succeeded in flying, with wings made by his father, using feathers and beeswax.

Unfortunately, Icarus ignored his father’s warnings, and he flew too close to the sun, melting the wax, and he fell into the sea and drowned. His legs can be seen in the water at the bottom right.

“The Triumph of Bacchus” by Diego Velázquez

“The Triumph of Bacchus” by Diego Velázquez depicts Bacchus surrounded by drunks. The work represents Bacchus as the god who rewards men with wine, releasing them from their problems.

Bacchus was considered an allegory of the liberation of man from the slavery of daily life. Commissioned by King Philip IV, Velázquez had studied the King’s collection of Italian paintings and especially the treatment of mythological subjects.

In this work, Velázquez adopted a realist treatment of a mythological subject, an approach he pursued during his career.

The composition is divided into two halves. On the left, is the luminous Bacchus figure, and the character behind him is represented in the traditional loose robes used for depictions of classical myth.

The idealization of the Bacchus’s face is highlighted by the light which illuminates him in a classical style. The right side of the composition presents drunkards of the streets that invite the viewer to join their party.

There is no idealization present in their darker worn-out faces who wear the contemporary costume of poor people in 17th-century Spain. The figure kneeling in front of the Bacchus is younger and better dressed than the others, with a sword and boots.

The light which illuminates Bacchus is absent on the right side. There are also various elements of naturalism in this work, such as the bottle and pitcher, which appear on the ground.

“Dido Building Carthage” by J. M. W. Turner

“Dido Building Carthage” by J. M. W. Turner depicts the classic story from Virgil’s Aeneid in which Dido, the figure in blue and white on the left, is directing the builders of the new city of Carthage.

The figure in front of her, wearing armor, is her Trojan lover Aeneas. The children playing with a toy boat symbolize the future naval power of Carthage, and the tomb of her dead husband Sychaeus, on the right bank of the estuary, foreshadows the eventual destruction of Carthage by the Roman descendants of Aeneas.

The painting was first exhibited at the Royal Academy summer exhibition in 1815 and was widely admired, but Turner kept the picture until his death and left it to the nation in the Turner Bequest.

“Venus and Mars” by Sandro Botticelli

“Venus and Mars” by Sandro Botticelli portray Venus, the Roman goddess of love, and Mars, the god of war, as a coupled reclining in a forest setting, surrounded by playful baby satyrs.

It is an allegory of beauty and bravery, representing an ideal view of sensuous marriage and love. Based on the subject of the composition and the unusual wide format of this masterpiece, the painting was probably intended to commemorate a wedding. It was created to be set into a piece of furniture to adorn the bedroom of the bride and groom.

Venus watches Mars sleep while two infant satyrs play with Mars’ weapons of war. One of the satyrs blows a small conch shell in Mars’ ear to wake him.

The implication is that the couple has made love, and the male has fallen asleep. In this context, the lance and conch can also be read as sexual symbols.

“Primavera” by Sandro Botticelli

“Primavera” by Sandro Botticelli depicts a group of figures from classical mythology in a garden, brought together by Botticelli as an allegory based on the promised renewal of Spring and the seasons.

The meaning of this masterpiece is debated by art historians, as the composition draws from many classical and Renaissance literary sources.

Viewed from right to left, at the right is Zephyrus, the god of the west wind, who kidnaps the nymph Chloris, whom he later marries, and she becomes the goddess of Spring.

Chloris, the nymph overlaps Flora, the goddess she transforms into, as her future state, of Flora, is shown scattering or collecting roses from the ground. In the center stands Venus, gazing at the viewer and appears to be blessing the scene or cycle.

The trees behind her form a broken arch, and the blindfolded Cupid aims his bow to the left. On the left of the painting, the Three Graces, are joining hands in a dance; however, one of them has noticed Mercury.

She is the target of cupids arrow. At the left Mercury, clothed in red with a sword, and a helmet raises his rod towards the emerging clouds.

“Bacchus and Ariadne” by Titian

“Bacchus and Ariadne” by Titian depict Bacchus, the god of wine, emerging with his followers from the right of the scene and according to myth, falling in love at first sight with Ariadne.

Titian shows Bacchus leaping from his chariot to protect Ariadne, who has been abandoned on a Greek island and deserted by her lover Theseus, whose ship sails away to the far left of the picture.

The first commission for this painting was given to Raphael, who unfortunately died young in 1520, and Titian was given the opportunity to paint this mythological subject during 1522 for a wealthy patron.

“The Rape of Europa” by Titian

The “Rape of Europa” by Titian is a mythological painting of the story of the abduction of Europa by Zeus, painted about 1560 – 62.

In Greek mythology, Europa was the mother of King Minos of Crete, a woman with Phoenician origins, after whom the continent of Europe was named.

The painting depicts the story of her abduction by Zeus, who is in the form of a white bull.

This myth was originally a Cretan story, and many of the love-stories concerning Zeus originated from even more ancient myths describing his marriages with goddesses.

“Perseus and Andromeda” by Titian

“Perseus and Andromeda” by Titian dramatically depict the Greek mythological story of Andromeda.

Perseus is portrayed as attacking the sea monster, who turns to attack the hero, while Andromeda’s white body is contrasted against the dark undercliff and portrayed as pure innocence.

In Greek mythology, Andromeda was the daughter of the Ethiopian King Cepheus and Queen Cassiopeia. Queen Cassiopeia was beautiful, but the vain and her hubris led her to boast that Andromeda is more beautiful than the sea nymphs. T

he sea nymphs were the daughters of Poseidon, the god of the sea, and when the nymphs heard of her claims, they protested to their father.

In retaliated Poseidon calling up a sea monster to wreak havoc on Ethiopia, placing the kingdom at risk. In response, the Queen, together with the King, decided to sacrifice her daughter, Princess Andromeda, to the monster.

“Perseus and Andromeda” by Joachim Wtewael

Perseus is depicted flying above on his winged horse Pegasus. Perseus used his sword to attack the sea monster, who turns to attack the hero. Andromeda’s white body is contrasted with symbols of death on the ground and depicted as pure innocence.

In Greek mythology, Andromeda was the daughter of the Ethiopian King Cepheus and Queen Cassiopeia. The beautiful but the vain Queen, Cassiopeia’s hubris led her to boast that Andromeda is more beautiful than the sea nymphs, who were the daughters of Poseidon, the god of the sea.

When the nymphs heard of her claims, they protested to their father, who retaliated by calling up a sea monster called Cetus to wreak havoc on Ethiopia, placing the kingdom at risk.

In response, the Queen, together with the King, decided to sacrifice her daughter, Princess Andromeda, to the monster.

“Perseus and Andromeda” by Giuseppe Cesari

“Perseus and Andromeda” by Frederic Leighton

“Perseus with the Head of Medusa” by Antonio Canova

Perseus, with the Head of Medusa by Antonio Canova, depicts the Greek mythological story of Perseus beheading Medusa, a hideous woman-faced

Gorgon whose hair was turned to snakes and anyone that looked at her was turned to stone.

Perseus stands naked except for a cape hanging from his arm, sandals and a winged hat, triumphant with Medus’s snakey head in his raised hand. Museum: Metropolitan Museum of Art – MET

“Cymon and Iphigenia” by Frederic Leighton

“Cymon and Iphigenia” by Frederic Leighton depicts a mythological story about “Cymon” which means “the brute,” who one day while walking in the woods, discovered a young woman, “Iphigenia,” fast asleep in a meadow under a tree, and her beauty awoke his soul.

This parable of grace soothing the savage beast inverts the myth of “Sleeping Beauty,” in which a man awakens a young woman to adulthood. In this mythological story, the woman inspires the male, brute. Museum: Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

“Aurora and Cephalus” by François Boucher

“Aurora and Cephalus” by François Boucher depicts Aurora, the goddess of dawn, waking up the mortal Cephalus from sleep.

According to Roman mythology and Latin poetry, Aurora has fallen madly in love with Cephalus and who is one of her human lovers. In this Rococo masterpiece, the blue sky is tinged with pink, and the dawn can be seen with the light above her head.

Furthermore, Aurora’s etherealism or heavenly aspects are symbolized by her chariot, her flying horses, and the cherubs.

Especially relevant is Cephalus’s mortality and roots to earth, which is signified by his dog, and his hunting catch in the bottom left. Museum: Yamazaki Mazak Museum of Art

“The Lady of Shalott” by John William Waterhouse

“The Lady of Shalott” by John William Waterhouse portrays the ending of Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s 1832 poem of the same name.

The scene shows the plight of a young woman from Arthurian legend, who yearned with unrequited love for the knight Sir Lancelot but was isolated under a curse in a tower near King Arthur’s Camelot. Museum: Tate Britain

“Lady Lilith” by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

“Lady Lilith” by Dante Gabriel Rossetti depicts Lilith, who is a figure from Jewish mythology and is portrayed as an iconic, Amazon-like female with long, flowing hair. The name ‘Lilith’ is derived from the Babylonian Talmud.

It refers to a dangerous demon of the night, associated with the seduction of men and the murder of children.

The character is thought to have been derived from the stories of female demons in ancient Mesopotamian religion, found in the cuneiform texts of Sumer, the Akkadian Empire, Assyria, and Babylonia. Museum: Delaware Art Museum

“Circe Invidiosa” by John William Waterhouse

“Circe Invidiosa,” which in Latin means “Jealous Circe” by John William Waterhouse, portrays Circe, poisoning the water to turn Scylla, her rival into “a hideous monster.”

Circe is a goddess of magic, or sometimes an enchantress from Greek mythology, and Scylla was a beautiful nymph who gets turned into the monster.

In Latin, invidia is the sense of envy, a “looking upon” associated with the evil eye. Invidia or envy is one of the Seven Deadly Sins in Christian belief. Invidia is also the Roman name for the ancient Greek goddess, Nemesis.

In this painting, Waterhouse has expertly invested his main subject with an aura of menace, with deep greens and blues and the echo of straight vertical lines emphasizing the inevitability of her intent. Museum: Art Gallery of South Australia

“Hylas and the Nymphs” by John William Waterhouse

“Hylas and the Nymphs” by John William Waterhouse portrays the abduction of Hylas by water nymphs. Hylas, according to classical mythology, was as a youth who served as Heracles’ companion and servant.

Hylas was kidnapped by nymphs of the spring, who had fallen in love with him, and he vanished without a trace.

According to one ancient author, Heracles never found Hylas because he had fallen in love with the nymphs and remained “to share their power and their love.” Museum: Manchester Art Gallery

“Pygmalion and Galatea” by Jean-Léon Gérôme

“Pygmalion and Galatea” by Jean-Léon Gérôme depicts the story from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, where the sculptor Pygmalion kisses his ivory statue Galatea, after the goddess, Aphrodite has brought her to life.

In Ovid’s narrative, Pygmalion was a Cypriot sculptor who carved a woman out of ivory. Galatea “she who is milk-white” is the name of the statue carved by Pygmalion. His figure was so beautiful and realistic that he fell in love with it.

On Aphrodite’s festival day, Pygmalion made offerings at the altar of Aphrodite, and he made a wish. When he returned home, he kissed his ivory statue and found that its lips felt warm.

Aphrodite had granted Pygmalion’s request; the ivory sculpture changed to a woman with Aphrodite’s (or Venus’ the Roman equivalent) blessing. Museum: Metropolitan Museum of Art – MET

“The Judgment of Paris” by Peter Paul Rubens (Prado Museum)

“The Judgment of Paris” by Peter Paul Rubens shows Rubens’ version of idealized feminine beauty, with the goddesses Venus, Minerva, and Juno on righthand.

Mercury accompanies Paris on the left side. “The Judgement of Paris” is a story from Greek mythology. It is one of the events that led to the Trojan War.

In the later Roman version of the story, it was also one of the events that led to the foundation of Rome.

The story of the Judgement of Paris offered artists the opportunity to depict a beauty contest between three beautiful female nudes. Museum: Prado Museum, Museo del Prado

“The Judgement of Paris” (The National Gallery, London)

This Greek story starts when Zeus held a banquet in celebration of the marriage of Peleus and Thetis, the parents of Achilles. Unfortunately, Eris, the goddess of discord, was not invited, as she would have made the party unpleasant for everyone.

Eris arrived uninvited and angry at the celebration with a golden apple, which she threw into the proceedings as a prize of beauty. Three goddesses claimed the apple Hera (Juno), Athena (Minerva), and Aphrodite (Venus).

They asked Zeus to judge which of them was fairest, reluctant to decide himself; he declared that Paris, a Trojan mortal, would judge their cases. Museum: National Gallery, London

“Battle of the Amazons” by Peter Paul Rubens

“Battle of the Amazons” by Peter Paul Rubens depicts a battle of the warlike women called Amazons from Ancient Greek mythology. I

n this depiction, the Amazons are losing the fight with the Greek horsemen charging headlong into combat and the Amazons falling in defeat.

Rubens has created a whirlwind composition that is a dazzling Baroque masterpiece.

Rubens’s artistic narrative is anchored around the arch of the bridge, which forms a center that encircles the flow of movement of the combatants.

The surging movement throws the opposing forces together with the Amazons being hurled from their horses down into the river. Museum: Alte Pinakothek

“Achilles on Skyros” in Art

Achilles on Skyros is an episode in the myth of Achilles, the Greek hero from the Trojan War.

The core myth describes that rather than allow her son Achilles to die at Troy as prophesied, the nymph Thetis sent him to live at the court of Lycomedes, King of Skyros.

Achilles was persuaded to disguise himself as a girl at the court of the King of Skyros. Thus he joined the daughters of the King as a lady-in-waiting to evade the prophecy.

Achilles then fell in love with one of the princesses and had an affair with Deidamia, one of the daughters of King.

“Achilles on Skyros” by Nicolas Poussin – Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

“The Discovery of Achilles among the Daughters of Lycomedes” by Jan de Bray – National Museum, Warsaw

“Discovery of Achilles on Skyros” by Nicolas Poussin – Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

“Odysseus recognizes Achilles amongst the daughters of Lycomedes” by Louis Gauffier – Nationalmuseum

Leda and the Swan in Art

“Leda and the Swan” depicts the ancient story and subject from Greek mythology. The story tells how the ancient Greek king of gods Zeus, in the form of a swan, seduces Leda.

In some versions of the myth, Zeus rapes Leda, and one of the children that Leda bore was a beautiful daughter who became known later as Helen of Troy.

In the Iliad and the Odyssey, Helen is the daughter of Zeus and of Leda. Leda was the wife of the Spartan king Tyndareus. Euripides’ play of Helen, written in the late 5th century BC, provides the earliest detailed account of Helen’s birth.

Zeus, in the form of a swan, was chased by an eagle, and he sought refuge with Leda. The swan gained her affection, and the two mated. Leda then produced two eggs from which four children emerged.

Helen was one of the children, who became the most beautiful woman in the ancient world and whose face launched one thousand ships.

- “Leda and the Swan” by Paul Cézanne – Barnes Foundation

- “Leda and the Swan” by Jerzy Hulewicz – National Museum, Warsaw

- “Leda and the Swan” after Michelangelo – National Gallery, London

- “Leda and the Swan” by Cesare da Sesto, after Leonardo da Vinci – Wilton House

- “Leda and the Swan” After Leonardo da Vinci, Attributed to Il Sodoma – Galleria Borghese

- “Leda and the Swan” by Francesco Melzi, after Leonardo da Vinci – Uffizi Gallery

Diana and Callisto in Art

“Jupiter and Callisto” depicts Jupiter, disguised as Diana, goddess of the hunt, embraces the nymph Callisto. In Greek mythology, Callisto was a beautiful young nymph, which attracted Zeus (Jupiter) attention.

Zeus transformed himself into the figure of Diana to seduce and raped her in this disguise. Callisto became pregnant, and when this was eventually discovered, she was expelled as a follower from Diana’s group, after which a furious Hera, the wife of Zeus, transformed her into a bear.

Later, just as she was about to be killed by her son when he was hunting, she was set among the stars as Ursa Major “the Great Bear.” She was the bear-mother of the Arcadians, through her son Arcas by Zeus.

- “Jupiter and Callisto” Attributed to Karel Philips Spierincks – Philadelphia Museum of Art

- “Jupiter in the Guise of Diana, and the Nymph Callisto” by François Boucher – Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

- “Diana and Callisto” by Titian – National Gallery, London and National Gallery of Scotland

- “Diana and Callisto” by Peter Paul Rubens – Museo del Prado

- “Diana and Callisto” by Sebastiano Ricci – Gallerie dell’Accademia

- “Diana and Callisto” by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo – Gallerie dell’Accademia

- “Landscape with Diana and Callisto” by Cornelis van Pulenburg – State Hermitage Museum

- “Diana Discovering the Pregnancy of Callisto” Attributed to Paul Brill – Musée du Louvre

“Pallas and the Centaur” by Sandro Botticelli

“Pallas and the Centaur” by Sandro Botticelli depicts a centaur with bow and arrows and a female figure holding a very elaborate halberd. She is clutching the centaur’s hair, and he is submissive to her.

The female character was called Camilla in the earliest record of the painting, but later she is called Minerva. Minerva was the Roman equivalent of Pallas Athene, and this description of “Pallas” for the woman has been adopted as her name.

The life-size figures are from classical mythology and form an allegory. Centaurs are associated with uncontrolled passion, lust, and sensuality, and part of the meaning of the painting is about the submission of passion to reason.

An elaborate halberd was a weapon carried by guards rather than on the battlefield. The centaur appears to have been arrested while preparing to shoot his bow. Various other historical, political, and philosophical purposes have also been proposed for this image. Museum: Uffizi Gallery

Greek Mythology God and Goddesses

Popular Egyptian Art – Virtual Tour

- Nefertiti Bust

- Narmer Palette

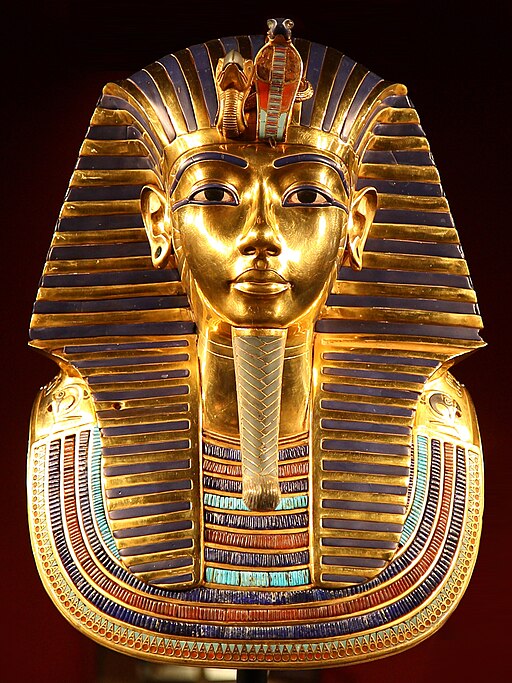

- Tutankhamun’s Mask

- Merneptah Stele

- Standing Figure of Nefertiti

- A house altar showing Akhenaten and Nefertiti with their children

- Relief Portrait of Akhenaten

- The Rosetta Stone

- The Battlefield Palette 3100 BC

- Quartzite Head of the Egyptian Pharaoh Amenhotep III

- Colossal Granite Statue of Amenhotep III

- Hunters Palette

- Tomb of Nebamun

- The Temple of Dendur

- The Sphinx of Hatshepsut

- William the Faience Hippopotamus

- Shawabti of King Senkamanisken

- Younger Memnon (Ramesses II)

- Pillar of Ramsesemperre, Royal Cupbearer and Fanbearer

- Relief of Hormin with a Weighing of the Heart

- Relief of Horemheb with Nubian Prisoners

Explore Museums with Egyptian Artifacts – Virtual Tour

- Egyptian Museum, Cairo

- The British Museum

- Neues Museum, Berlin

- Egyptian Museum of Berlin, Neues Museum, Berlin

- Metropolitan Museum of Art – MET, New York, USA

- Penn Museum

- The Archaeological Civic Museum of Bologna

Mesopotamian Art – Virtual Tour

- Gudea, Prince of Lagash

- Sumerian Standing Male Worshiper

- Human-Headed Winged Bull

- Gilgamesh Flood Tablet

- Ishtar Gate

- Cuneiform Tablet

- Cyrus Cylinder

- Lion Hunting Scene – 750 BC

- Lion Hunt Relief from Nimrud

- Temple of Ashur Water Basin

- Victory Stele of Esarhaddon

- The Lion Hunt

- Cyrus Cylinder

- Royal Game of Ur

- Gilgamesh Flood Tablet

- Stela of Shamshi-Adad V

- Sumerian Standing Male Worshiper

- Head of a Beardless Royal Attendant – Eunuch

- Human-Headed Winged Bull (Lamassu)

- Law Code of Hammurabi

- Gudea, Prince of Lagash

Islamic Art – Virtual Tour

- Tile – Building Ceramic – Iran 13th – 14th Century

- Islamic Astrolabe

- Islamic Prayer Niche

- Blue Qur’an

- Marble Jar of Zayn al-Din Yahya Al-Ustadar

- The Damascus Room

- Desert Place of Mshatta Facade

Explore – Virtual Tour

- Artists and their Art

- Popular Paintings

- Portraits

- Mythological Art

- Christian Art

- Buddhist Art

- Ancient Egyptian Art

Norse Mythology Explained In 15 Minutes

Greek Gods Explained In 12 Minutes

What Is Myth? Crash Course World Mythology

~~~

“We hunger to understand,

so we invent myths about how we imagine the world is constructed

– and they are, of course, based upon what we know.”

– Carl Sagan

~~~

Photo Credit: By Giovan Battista Gaulli – Beauvais, Musée départemental de l’Oise ([1] – Olio su tela, cm. 149 x 222) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Popular this Week

Sponsor your Favorite Page

Sponsor your Favorite Page SEARCH Search for: Search Follow UsJoin – The JOM Membership Program

Sponsor a Masterpiece with YOUR NAME CHOICE for $5

Share this:

- Tweet