The Bull-Leaping Fresco is a restored stucco painting situated initially on the upper-story portion of the east wall of the palace at Knossos in Crete. The fresco is one of a few surviving depictions of the act of jumping over bulls.

The Bull-Leaping Fresco depicts three individuals, two women one at the front, one at the back, and a male youth shown balancing on the bull. The techniques employed and the reasons for the ceremony remain obscure.

The gender of the individuals is identified according to the Minoan art convention of painting women with pale skin and men with dark skin. Their clothes and jewelry identify the participant’s high status.

The bull is shown in what is called the “Mycenaean Flying Leap,” which means it is in full gallop. The artist has shown the bull’s body in an elongated form with extended legs to indicate movement.

The bull’s horns are being firmly held by the woman in front in preparation to leap over the bull, or it may be an earlier episode while the bull was stationary.

The boy may be in a balancing position, rather than tumbling, as he holds the flanks of the bull with both hands.

The composition may not show a chronological sequence, as the individuals are all different. Instead, the figures may be disconnected in time and space, but have been superimposed to provide an overall impression of a scene.

This scene was familiar and symbolic to Minoan viewers, but not to a modern audience from a different culture.

The central figure of the Bull-Leaping Fresco

The modern perception is that the leaper goes over the bull in an upside-down position, whether diving from above, leaping up from below, maybe a modern misunderstanding of the fresco’s symbolism.

Modern attempts to recreate the leaping on modern cattle have resulted only in several deaths. The modern bull is too fast, powerful, and aggressive to allow the seizure of the horns, much less the neck toss for acrobatics.

Moreover, that toss is a hook to the side, not a neat backward boost. The bull usually attempts to skewer the human with one horn, without the cooperation in the style of the frescos.

It is possible to leap over small bulls without touching them, even as they charge, and such spectacles still practiced in France may be the ultimate source of the icon.

A stationary bull might be touched or pushed on the way over, but pressing on a bull in motion would lead to a violent collision.

The same bull-leaping scene appears in miniature in “seal stones” from the Minoan culture.

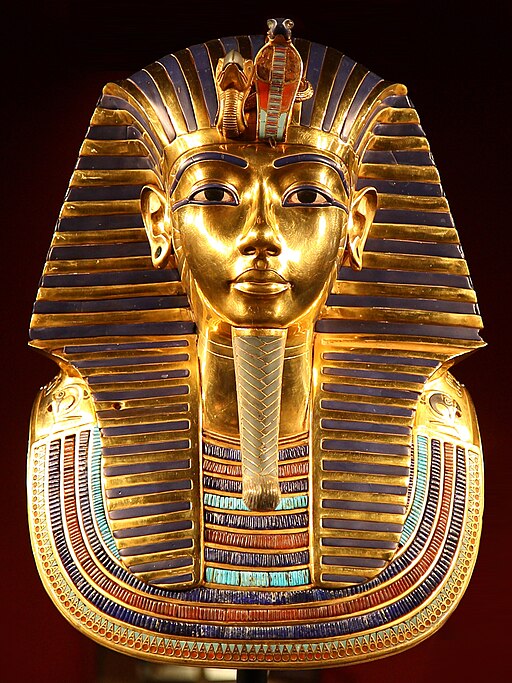

The Symbolism of the Bull

Minoan horn-topped altars, called “Horns of Consecration,” are represented in seal impressions and have been found as far afield as Cyprus. Minoan sacred symbols included the bull and its horns of consecration.

Bull festivals must have been significant to the culture to have been depicted in Palace fresco and inscribed in miniature seals.

“Horns of Consecration” describes the symbol, ubiquitous in Minoan civilization, that represents the horns of the sacred bull.

Horns of consecration in stone or clay were placed on the roofs of buildings, on tombs and shrines, probably as signs of the sanctity of the structure.

The survival of bull sports into classical and modern times may offer clues from festival events similar to bull-dogging. First, the bull in the ring is baited by riders to exhaust him.

Then a rider comes up beside him, leaps on his back, seize the horns, and falling to one side, twists the head, bringing down the tired bull.

Why the Minoans participated in this ritual is not clear, but it may be related to peer status and social reward.

The figure in the left of the Bull-Leaping Fresco

Minoan Frescos

The Bull-Leaping Fresco was painted on stucco relief scenes and are classified as plastic art. They were challenging to produce as the artist had to simultaneous mold and painting of fresh stucco.

The flakes of the destroyed panels fell to the ground from the upper story during the destruction of the palace, probably by an earthquake, during the Late Minoan period. By that time, the east stairwell, near which they fell, was disused, being partly ruinous.

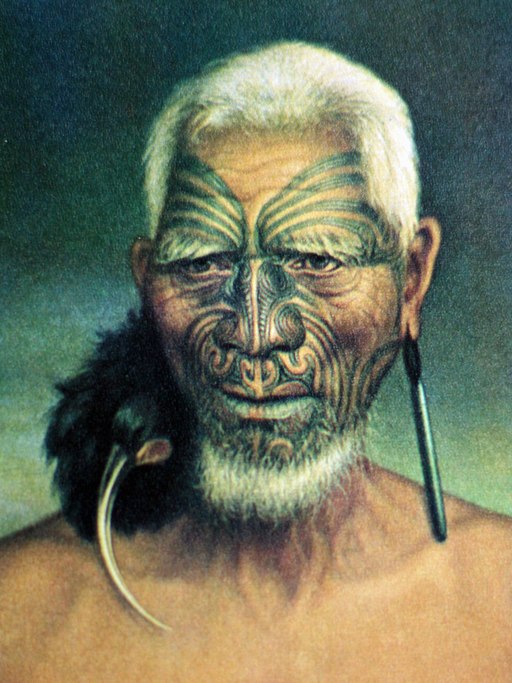

Arthur Evans, the archaeologist who first excavated the site, recognized that depictions of bulls and bull-handling had a long tradition represented by many examples in art, not only at Knossos and other sites on Crete.

Depictions of bulls were shared across the Aegean, mainland Greece, and with traditions even more ancient in Egypt and the Middle East.

At Knossos, Evens distinguished “bull-grappling scenes” as an act especially significant to Minoan culture, highlights humanity’s attempt to master nature.

Minoan Civilization

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age Aegean civilization on the island of Crete and some other Aegean Islands, flourishing from c. about 3000 BC to a period of decline, ending around 1100 BC.

The Minoan civilization is considered the first advanced civilization in Europe, leaving behind massive building complexes, tools, artwork, writing systems, and a network of trade.

The civilization was rediscovered at the beginning of the 20th century through the work of British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans.

The name “Minoan” derived from the mythical King Minos and was coined by Evans, who identified the site at Knossos with the labyrinth and the Minotaur.

The Minoan civilization is particularly notable for its extensive and elaborate palaces up to four stories high, featuring decorations with frescoes.

Through their traders and artists, the Minoans’ cultural influence reached beyond Crete to the Cyclades, the Old Kingdom of Egypt, copper-bearing Cyprus, Canaan, and the Levantine coast and Anatolia.

Some of the best Minoan art is preserved in the city of Akrotiri on the island of Santorini, which was destroyed by the Minoan eruption.

The reasons for the decline of the Minoan civilization are unclear, though theories include Mycenaean invasions from mainland Greece and the major volcanic eruption of Santorini.

The figure on the right in the Bull-Leaping Fresco

Knossos

Knossos is the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete and has been called Europe’s oldest city.

Settled as early as the Neolithic period, the name Knossos survives from ancient Greek references. The palace of Knossos eventually became the ceremonial and political center of the Minoan civilization and culture.

The palace was abandoned at some time at the end of the Late Bronze Age, c. 1,380–1,100 BC, the reason why is unknown.

In its peak, the palace and surrounding city boasted a population of 100,000 people shortly after 1,700 BC.

In Greek mythology, King Minos dwelt in a palace at Knossos. He had Daedalus construct a labyrinth, a vast maze in which to retain his son, the Minotaur. The name “Knossos” was adopted for the site by English archaeologist Arthur Evans.

The reconstructed “Horns of Consecration” at Knossos

Arthur Evans

Arthur Evans (1851 – 1941) was an English archaeologist and pioneer in the study of Aegean civilization in the Bronze Age. He is most famous for unearthing the palace of Knossos on the Greek island of Crete.

Based on the structures and artifacts found there and throughout the eastern Mediterranean, Evans found that he needed to distinguish the Minoan civilization from Mycenaean Greece.

Evans was also the first to define Cretan scripts Linear A and Linear B, as well as earlier pictographic writing.

By 1903, most of the ruins of Knossos Palace were excavated, bringing to light an advanced city containing artwork and many examples of writing.

Painted on the walls of the palace were numerous scenes depicting bulls, leading Evans to conclude that the Minoans worship the bull.

After he finished excavations, Evans proceeded to have one of the palace rooms called the throne room due to the throne-like stone chair fixed in the room repainted.

While Evans based the recreations on archaeological evidence, some of the best-known frescoes from the throne room were recreated as a best guess rather than any scientific analysis, as that was not available at the time.

Bull-Leaping Fresco

- Artifact: Bull-Leaping Fresco

- Also: Taureador Fresco

- Date: 1450 BC

- Medium: Stucco panel with the scene in relief

- Dimensions: Height: 70 cm (27.5 in)

- Fide site: Knossos Palace, Crete – 1903

- Category: Historical Artifact and Art

- Museum: Heraklion Archaeological Museum

Bull-leaping Fresco

The Minoan Civilization

Highlights of the Heraklion Archaeological Museum

- Snake Goddess

- Phaistos Disc

- Bull-Leaping Fresco

Tour of the Greek Museums and Historic Sites

- Athens Museums

- Ancient Corinth Museums

- Delos Museums

- Delphi Museums

- Ancient Mycenae Museums

- Epidaurus Museums

- Heraklion, Crete Museums

- Meteora Museums

- Milos Museums

- Mystras Museums

- Olympia Museums

- Pella Museums

- Santorini Museums

- Thessaloniki Museums

The Art of Bull-Leaping

Art of the Aegean

Museums in Athens

- Acropolis Museum

- National Archaeological Museum

- Benaki Museum

- Goulandris Museum of Cycladic Art

- Byzantine and Christian Museum

- Hellenic Motor Museum

- National Historical Museum, Athens

- Museum of the Ancient Agora

- Syntagma Metro Station Archaeological Collection

- Numismatic Museum of Athens

- Athens War Museum

- Jewish Museum of Greece

- Athens University Museum

Bull Leaping Fresco

Minoans and Minoan Civilization

~~~

“I felt once more how simple and frugal a thing is happiness:

a glass of wine, a roast chestnut, a wretched little brazier, the sound of the sea.

Nothing else.”

– Nikos Kazantzakis

~~~

Photo Credit: ArchaiOptix / CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0); Heraklion Archaeological Museum / CC0; Wolfgang Sauber / CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0); ArchaiOptix / CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)

Popular this Week

Sponsor your Favorite Page

Sponsor your Favorite Page SEARCH Search for: Search Follow UsJoin – The JOM Membership Program

Sponsor a Masterpiece with YOUR NAME CHOICE for $5

Share this:

- Tweet